A couple days ago, I was asked a really interesting question by a client in the Pilates Method Fundamentals Class. What is neutral? It took me a second to answer the question. Well, is neutral relaxed? is it in the middle? Is it defined as the lack other movements or displacements like flexion (bending forward) extension (bending backwards), or rotation?

I guess it really depends on what part of the body we are referring to. When we talk about a peripheral joint (joint in an extremity like a leg or arm) being in "neutral" position, we are referring to a position of the joint, in the midrange of that particular joint's range of motion where it demands the least support from ligaments, connective tissue, and other non-muscular tissues around the joint. It is in this "neutral" position, that stress on the joint is at its minimum and the small, deep, local stabilizer muscles that surround the joint are best able to control the joint's movement. Mobilizer muscles are relaxed when a joint is in a supported, neutral position. Ideally, we would like to keep joints at or near their neutral position as much as possible to reduce wear and tear.

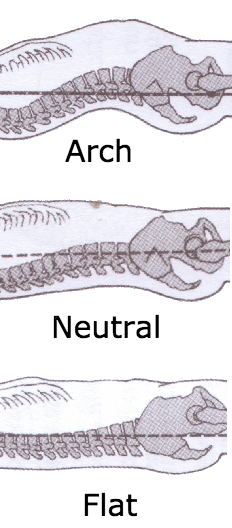

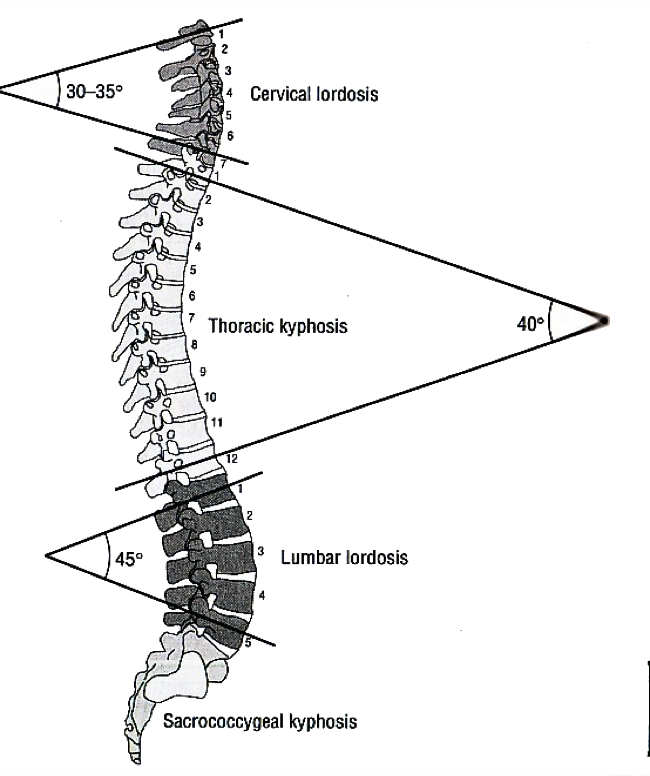

The spine is a bit more complicated. The spine can be divided into sections; the cervical (neck) spine, the thoracic spine (upper back, attached to ribs), lumbar (lower back) spine, and sacrum. Neutral means something slightly different for each section of the spine. The cervical and lumbar spine are both curved forward (the anatomical term is lordosis) where there is a space between the spine and the floor when you lie down on your back. The thoracic spine and the sacrum both are curved the opposite way (kyphosis) so that when you lie down on the floor, your upper back and sacrum (base of the spine) touch the floor.

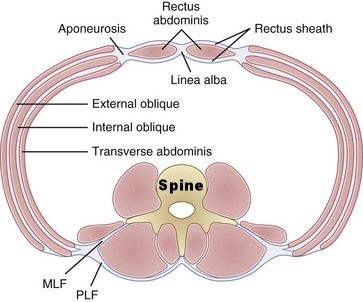

The spine actually requires quite a bit of support to remain "neutral." If we find a position where our ligaments are minimally stressed, muscles of our core have to be "engaged" and working. Neutral alignment in the spine is defined as having the center of C7 (the lowest cervical vertebral body/bone) over the very front, bottom corner of S1 (the very top of the sacrum). In case you don't have x-ray vision, alignment can be approximated by aligning the ear canals over the shoulders over the hips.

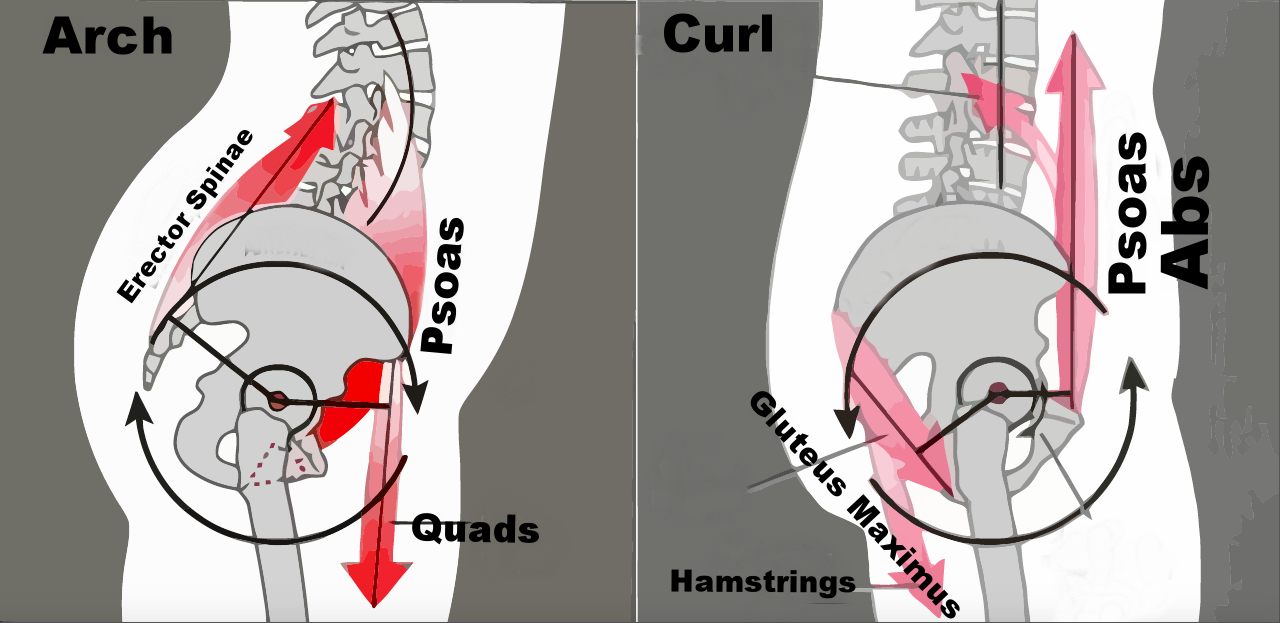

Finally, a "neutral" pelvis indicates that the anterior superior iliac spines (the bony part of your pelvis just above your groin that you feel on either side of your lower abdomen) and pubic symphysis (the bony part of the pelvis in the midline of the body just above the genitals) fall in the same vertical plane/line.

Once you can position your body as close to neutral as you can, I try to distinguish between muscles being "engaged" vs core muscles being rigid. To use volume/sound as an analogy, engaged means that the muscles are working at a hum. Rigid muscles are working at a shout. You want your body to be supported and muscle to be awake, but you don't want to be stiff and full of tension. The goal is to have neutral body position that is supported and still responsive to movement. More on movement in a future posts.